Dialectical materialism

| Part of a series on |

| Marxist theory |

|---|

|

|

Theoretical works

The Communist Manifesto

A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy Das Kapital The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoleon

GrundrisseThe German Ideology Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844

Theses on Feuerbach |

|

Social sciences

Alienation · Marx's theory of the state · Bourgeoisie

Base and superstructure Class consciousness Commodity fetishism Communism · Socialism Exploitation · Human nature Ideology · Proletariat Reification · Cultural hegemony Relations of production |

|

Economics

Marxian economics

Scientific socialism Economic determinism Labour power · Law of value Means of production Mode of production Productive forces Surplus labour · Surplus value Transformation problem Wage labour |

|

History

Marx's theory of history

Historical materialism Historical determinism Anarchism and Marxism Capitalist production Class struggle Dictatorship of the proletariat Primitive capital accumulation Proletarian revolution Proletarian internationalism World revolution Stateless communism |

|

Philosophy

Marxist philosophy

Dialectical materialism Historical materialism Philosophy in the Soviet Union Marxist philosophy of nature Marxist humanism Marxist feminism Western Marxism Analytical Marxism Libertarian Marxism Marxist autonomism Marxist geography Marxist literary criticism Structural Marxism Post-Marxism Young Marx |

|

People

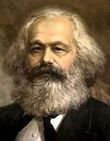

Karl Marx · Friedrich Engels

Karl Kautsky · Eduard Bernstein Vladimir Lenin · Joseph Stalin Georgi Plekhanov · Mao Zedong Rosa Luxemburg · Leon Trotsky · Louis Althusser · Georg Lukács Antonio Gramsci · Antonie Pannekoek more |

|

Criticism

Criticisms of Marxism

|

|

Categories

All categorised articles

|

Dialectical materialism is a strand of Marxist theorizing, predominant in the Soviet Union, composed of a synthesis of Hegel's dialectics and Feuerbach's materialism, based upon an interpretation of Karl Marx's work. According to certain followers of Karl Marx's thinking, it is the philosophical basis of Marxism, although this remains a controversial assertion due to the disputed status of science and naturalism in Marx's thought.

Dialectical materialism is the philosophy of Karl Marx which advocated that history advanced as a result of material or economic forces which would eventually lead to the creation of a classless society.

Contents |

The term

Dialectical materialism was coined in 1887 by Joseph Dietzgen, a socialist tanner who corresponded with Marx both during and after the failed 1848 German Revolution. Dietzgen had himself discovered dialectical materialism independently of Marx and Friedrich Engels. Casual mention of the term is also found in Kautsky's Frederick Engels[1], written in the same year. Marx himself had talked about the "materialist conception of history", which was later referred to as "historical materialism" by Engels. Engels further exposed the "materialist dialectic" — not "dialectical materialism" — in his Dialectics of Nature in 1883. Georgi Plekhanov, the father of Russian Marxism, later introduced the term dialectical materialism to Marxist literature[2]. Stalin further codified it as Diamat and imposed it as the doctrine of Marxism-Leninism.

The term was not used by Marx in any of his works, and the actual presence of 'dialectical materialism' within his thought remains the subject of significant controversy, particularly regarding the relationship between dialectics, ontology and nature. For scholars working on these issues from a variety of perspectives see the works of Bertell Ollman, Chris Arthurs, Roger Albritton, and Roy Bhaskar.

Aspects

Dialectical materialism originates from two major aspects of Marx's philosophy. One is his transformation of Hegel's idealistic understanding of dialectics into a materialist one, an act commonly said to have "put Hegel's dialectics back on its feet". The other is his core idea that "the history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles" as stated in The Communist Manifesto in 1848.

Materialism is a radically empirical philosophy, akin to positivism, that is based in the conviction that all phenomena originate from a physical cause and can be understood and explained through natural science. According to materialism, matter is the total explanation for space, nature, man, society, history and every other aspect of existence. Materialism does not acknowledge any alleged phenomenon that cannot be perceived by the five senses such as the supernatural, God, etc. Some aspects of Marxism are informed by materialist philosophy.

Hegel

Dialectical materialism is essentially characterized by the thesis that history is the product of class struggles and follows the general Hegelian principle of philosophy of history, that is the development of the thesis into its antithesis which is sublated by the Aufhebung ("synthesis"). The term Aufhebung was not used by Hegel to describe his dialectics.[3] The Aufhebung conserves the thesis and the antithesis and transcends them both (Aufheben — this contradiction explains the difficulties of Hegel's thought).[4] Hegel's dialectics aims to explain the development of human history. He considered that truth was the product of history and that it passed through various moments, including the moment of error; error and negativity are part of the development of truth. Hegel's idealism considered history a product of the Spirit (Geist or also Zeitgeist — the "Spirit of the Time"). By contrast, Marx's dialectical materialism considers history as a product of material class struggle in society. Thus, theory has its roots in the materiality of social existence.

Materialism in dialectical materialism

Marx's doctoral thesis concerned the atomism of Epicurus and Democritus, which (along with stoicism) is considered the foundation of materialist philosophy. Marx was also familiar with Lucretius's theory of clinamen.

Materialism asserts the primacy of the material world: in short, matter precedes thought. Materialism, as with positivism, holds that the world is material; that all phenomena in the universe consist of "matter in motion," wherein all things are interdependent and interconnected and develop according to natural law; that the world exists outside us and independently of our perception of it; that thought is a reflection of the material world in the brain, and that the world is in principle knowable.

"The ideal is nothing else than the material world reflected by the human mind, and translated into forms of thought." --Karl Marx, Das Kapital, Vol. 1.

Marx endorsed this materialist philosophy against Hegel's idealism; he "turned Hegel's dialectics upside down." However, Marx also criticized classical materialism as another idealist philosophy. According to the famous Theses on Feuerbach (1845), philosophy had to stop "interpreting" the world in endless metaphysical debates, in order to start "changing" the world, as was being done by the rising workers' movement observed by Engels in England (Chartist movement) and by Marx in France and Germany. Thus, dialectical materialists tend to accord primacy to class struggle. The ultimate sense of Marx's materialist philosophy is that philosophy itself must take a position in the class struggle based on objective analysis of physical and social relations. Otherwise, it will be reduced to spiritualist idealism, such as the philosophies of Kant or Hegel, which are only ideologies, that is the material product of social existence.

Dialectics in dialectical materialism

Dialectics is the science of the general and abstract laws of the development of nature, society, and thought. Its principal features are:

- The universe is an integral whole in which things are interdependent, rather than a mixture of things isolated from each other.

- The natural world or cosmos is in a state of constant motion:

- "All nature, from the smallest thing to the biggest, from a grain of sand to the sun, from the protista to man, is in a constant state of coming into being and going out of being, in a constant flux, in a ceaseless state of movement and change." --Friedrich Engels, Dialectics of Nature.

- Development is a process whereby insignificant and imperceptible quantitative changes lead to fundamental, qualitative changes. Qualitative changes occur not gradually, but rapidly and abruptly, as leaps from one state to another. A simple example from the physical world is the heating of water: a one degree increase in temperature is a quantitative change, but between 99 and 100 degrees there is a qualitative change - water to steam.

- "Merely quantitative differences, beyond a certain point, pass into qualitative changes." --Karl Marx, Capital, Vol. 1.

- All things contain within themselves internal dialectical contradictions, which are the primary cause of motion, change, and development in the world. It is important to note that 'dialectical contradiction' is not about simple 'opposites' or 'negation'. For formal approaches, the core message of 'dialectical opposition / contradiction' must be understood as 'some sense' opposition between the objects involved in a directly associated context.

For the application of the dialectic to history see Historical materialism.

Engels' laws of dialectics

As mentioned above, Engels determined three laws of dialectics from his reading of Hegel's Science of Logic[5]. Engels elucidated these laws in his work Dialectics of Nature:

- The law of the unity and conflict of opposites;

- The law of the passage of quantitative changes into qualitative changes;

- The law of the negation of the negation

The first law was seen by both Hegel and Lenin as the central feature of a dialectical understanding of things[6][7] and originates with the ancient Ionian philosopher Heraclitus.[8]

The second law Hegel took from Aristotle, and it is equated with what scientists call phase transitions. It may be traced to the ancient Ionian philosophers (particularly Anaximenes), from whom Aristotle, Hegel and Engels inherited the concept. For all these authors, one of the main illustrations is the phase transitions of water. There has also been an effort to apply this mechanism to social phenomena, whereby population increases result in changes in social structure [9].

The third law is Hegel's own. It was the expression through which (amongst other things) Hegel's dialectic became fashionable during his life-time.

In drawing up these laws, Engels presupposes a holistic approach outlined above and in Lenin's three elements of dialectic below, and emphasizes elsewhere that all things are in motion.[10]

Lenin's elements of dialectics

After reading Hegel's Science of Logic in 1914, Lenin made some brief notes outlining three "elements" of logic.[11] They are:

| “ |

Such apparently are the elements of dialectics. |

” |

|

— Lenin, Summary of dialectics[12]

|

Lenin develops these in a further series of notes, and appears to argue that "the transition of quantity into quality and vice versa" is an example of the unity and opposition of opposites expressed tentatively as "not only the unity of opposites, but the transitions of every determination, quality, feature, side, property into every other [into its opposite?]."

History of dialectical materialism

Lenin's contributions

Dialectical materialism was first elaborated by Lenin in Materialism and Empiriocriticism in 1908 around three axes: the "materialist inversion" of Hegelian dialectics, the historicity of ethical principles ordered to class struggle and the convergence of "laws of evolution" in physics (Helmholtz), biology (Darwin) and in political economics (Marx). Lenin hence took position between a historicist Marxism (Labriola) and a determinist Marxism, close to "social Darwinism" (Kautsky). New discoveries in physics, including x-rays, electrons, and the beginnings of quantum mechanics challenged previous conceptions of matter and materialism. Matter seemed to be disappearing. Lenin disagreed:

'Matter disappears' means that the limit within which we have hitherto known matter disappears and that our knowledge is penetrating deeper; properties of matter are disappearing that formerly seemed absolute, immutable and primary, and which are now revealed to be relative and characteristic only of certain states of matter. For the sole 'property' of matter with whose recognition philosophical materialism is bound up is the property of being an objective reality, of existing outside of the mind.

Lenin was following on from the work of Friedrich Engels, who had noted that "with each epoch-making discovery even in the sphere of natural science, materialism has to change its form."[13] One of Lenin's challenges was distancing materialism as a viable philosophical outlook from what he referred to as the "vulgar materialism" expressed in statements like "the brain secretes thought in the same way as the liver secretes bile" (attributed to 18th century physician Pierre Jean Georges Cabanis, 1757-1808); "metaphysical materialism" (matter is composed of immutable, unchanging particles); and 19th-century "mechanical materialism" (matter was like little molecular billiard balls interacting according to simple laws of mechanics). Lenin's (and Engels') solution to this challenge was "dialectical materialism", where matter was understood in the broader sense of "objective reality" and consistent with new developments in science.

Lukács' additions

Georg Lukács, who had been minister of Culture in Béla Kun's short-lived Hungarian Soviet Republic (1919), published History and Class Consciousness in 1923. This book defined dialectical materialism as the knowledge of society as a whole, knowledge which in itself was immediately the class consciousness of the proletariat. In the first chapter, "What is Orthodox Marxism?", Lukács defined orthodoxy as the fidelity to the "Marxist method", and not to the "dogmas":

"Orthodox Marxism, therefore, does not imply the uncritical acceptance of the results of Marx’s investigations. It is not the ‘belief’ in this or that thesis, nor the exegesis of a ‘sacred’ book. On the contrary, orthodoxy refers exclusively to method. It is the scientific conviction that dialectical materialism is the road to truth and that its methods can be developed, expanded and deepened only along the lines laid down by its founders." (§1)

Lukács criticized revisionist attempts by calling for the return to this Marxist method. In much the same way that Althusser would later define Marxism and psychoanalysis as "conflictual sciences",[14] Lukács conceives "revisionism" and political splits as inherent to Marxist theory and praxis, insofar as dialectical materialism is, according to him, the product of class struggle:

"For this reason the task of orthodox Marxism, its victory over Revisionism and utopianism can never mean the defeat, once and for all, of false tendencies. It is an ever-renewed struggle against the insidious effects of bourgeois ideology on the thought of the proletariat. Marxist orthodoxy is no guardian of traditions, it is the eternally vigilant prophet proclaiming the relation between the tasks of the immediate present and the totality of the historical process." (end of §5)

Furthermore, he stated that "The premise of dialectical materialism is, we recall: 'It is not men’s consciousness that determines their existence, but on the contrary, their social existence that determines their consciousness.'... Only when the core of existence stands revealed as a social process can existence be seen as the product, albeit the hitherto unconscious product, of human activity." (§5) In line with Marx's thought, he thus criticized the individualist bourgeois philosophy of the subject, which founds itself on the voluntary and conscious subject. Against this ideology, he asserts the primacy of social relations. Existence — and thus the world — is the product of human activity; but this can be seen only if the primacy of social process on individual consciousness is accepted. He classified this consciousness as an effect of ideological mystification. His thesis doesn't entail that Lukács restrains human liberty on behalf of some kind of sociological determinism: to the contrary, this production of existence is the possibility of praxis.

However, this heterodox definition, that "orthodox Marxism" is fidelity to the Marxist "method", and not to "dogmas", was condemned, along with Karl Korsch's work, in July 1924, during the 5th Comintern Congress, by Grigory Zinoviev.

Dialectical Materialism as a Heuristic in Biology and Elsewhere

Some evolutionary biologists, such as Richard Lewontin and the late Stephen Jay Gould have employed dialectical materialism in their approach, playing a precautionary heuristic role in their work. For example, from Lewontin's perspective,

Dialectical materialism is not, and never has been, a programmatic method for solving particular physical problems. Rather, a dialectical analysis provides an overview and a set of warning signs against particular forms of dogmatism and narrowness of thought. It tells us, "Remember that history may leave an important trace. Remember that being and becoming are dual aspects of nature. Remember that conditions change and that the conditions necessary to the initiation of some process may be destroyed by the process itself. Remember to pay attention to real objects in time and space and not lose them in utterly idealized abstractions. Remember that qualitative effects of context and interaction may be lost when phenomena are isolated". And above all else, "Remember that all the other caveats are only reminders and warning signs whose application to different circumstances of the real world is contingent."[15]

Stephen Jay Gould shared similar views regarding a heuristic role for dialectical materialism. He wrote "Dialectical thinking should be taken more seriously by Western scholars, not discarded because some nations of the second world have constructed a cardboard version as an official political doctrine."[16] Further

when presented as guidelines for a philosophy of change, not as dogmatic percepts true by fiat, the three classical laws of dialectics embody a holistic vision that views change as interaction among components of complete systems, and sees the components themselves not as a priori entities, but as both products and inputs to the system. Thus, the law of "interpenetrating opposites" records the inextricable interdependence of components: the "transformation of quantity to quality" defends a systems-based view of change that translates incremental inputs into alterations of state; and the "negation of negation" describes the direction given to history because complex systems cannot revert exactly to previous states.[17]

This heuristic was also applied to the theory of punctuated equilibrium proposed by Niles Eldredge and Gould. They wrote "History, as Hegel said, moves upward in a spiral of negations," and that "puncuated equilibria is a model for discontinuous tempos of change (in) the process of speciation and the deployment of species in geological time." [18] They noted that "the law of transformation of quantity into quality", "holds that a new quality emerges in a leap as the slow accumulation of quantitative changes, long resisted by a stable system, finally forces it rapidly from one state into another," a phenomenon described in some disciplines as a paradigm shift. Apart from the commonly cited example of water turning to steam with increased temperature, Gould and Eldredge noted another analogy in information theory, "with its jargon of equilibrium, steady state, and homeostasis maintained by negative feedback," and "extremely rapid transitions that occur with positive feedback."[19]

Lewontin, Gould, and Eldredge, were thus more interested in dialectical materialism as a heuristic, than as a dogmatic form of 'truth', or as a statement of their politics. Nevertheless, they found a readiness for critics especially, to "seize upon" key statements[20] and quite literally portray punctuated equilibrium and exercises associated with it, such as public exhibitions, as a "Marxist plot"[21]

References

- ↑ http://www.marxists.org/archive/kautsky/1887/xx/engels.htm

- ↑ For instance, Plekhanov, The development of the monist view of history, (1895)

- ↑ Walter Kaufmann (1966). "§ 37". Hegel: A Reinterpretation. Anchor Books. ISBN 0268010684. OCLC 3168016. "Whoever looks for the stereotype of the allegedly Hegelian dialectic in Hegel's Phenomenology will not find it. What one does find on looking at the table of contents is a very decided preference for triadic arrangements. ... But these many triads are not presented or deduced by Hegel as so many theses, antitheses, and syntheses. It is not by means of any dialectic of that sort that his thought moves up the ladder to absolute knowledge."

- ↑ In particular, see Marx, The Poverty of Philosophy, chapter II, first observation, where he uses this formulation. Hegelians tend to attribute this formula to Marx's teacher - Heinrich Moritz Chalybäus - a Kantian who conflated Hegel's dialectic with the Fichtean triad thesis, antithesis, synthesis. It is suggested that after Marx's use of the phrase, Hegel has always been associated with the triad, which he rejected (cf Jon Stewart, ed (1996). "Introduction". The Hegel Myths and Legends. North-Western University Press. http://www.hegel.net/en/stewart1996.htm. Retrieved 2007-12-27.). However, one might cite Marx's explanation of the development of the dialectic in the cited passage of The Poverty of Philosophy: "This new [synthesis] unfolds itself again into two contradictory thoughts" which appears to be reaching beyond the limits of this misleading external triad to an inner inherent unfolding, more along the Hegelian lines.

- ↑ Engels, F. (7th ed., 1973). ). Dialectics of nature (Translator, Clements Dutt). New York: International Publishers. (Original work published 1940). See also Dialectics of Nature

- ↑ "It is in this dialectic as it is here understood, that is, in the grasping of oppositions in their unity, or of the positive in the negative, that speculative thought consists. It is the most important aspect of dialectic." Hegel, Science of Logic, § 69, (p 56 in the Miller edition)

- ↑ "The splitting of a single whole and the cognition of its contradictory parts is the essence (one of the "essentials", one of the principal, if not the principal, characteristics or features) of dialectics. That is precisely how Hegel, too, puts the matter." Lenin's Collected Works VOLUME 38, p359: On the question of dialectics.

- ↑ cf, for instance. 'The Doctrine of Flux and the Unity of Opposites' in the 'Heraclitus' entry in the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- ↑ Carneiro, R.L. (2000). The transition from quantity to quality: A neglected causal mechanism in accounting for social evolution. Proceedings of The National Academy of Sciences. Vol 97, No.23, pp.12926 - 12931. http://www.pnas.org/content/97/23/12926.full

- ↑ The discovery that heat was actually the movement of atoms or molecules was the very latest science of the period in which Engels was writing in his late period, in which what today we would express in terms of "energy" was just beginning to be grasped.

- ↑ Lenin's Summary of Hegel's Dialectics

- ↑ Lenin's Collected Works Vol. 38 pp 221 - 222, written while reading Book III, Section 3, Chapter 3 of The Science of Logic — “The Absolute Idea”

- ↑ http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1886/ludwig-feuerbach/ch02.htm Ludwig Feuerbach and the End of Classical German Philosophy

- ↑ Louis Althusser, "Marx and Freud", in Writings on Psychoanalysis, Stock/IMEC, 1993 (French edition)

- ↑ Beatty, J. (2009). "Lewontin, Richard". In Michael Ruse & Joseph Travis. Evolution: The First Four Billion Years. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. p. 685. ISBN 978-0-674-03175-3.

- ↑ Gould, Stephen Jay (1990). "Nurturing Nature". In …. An Urchin in the Storm: Essays About Books and Ideas. London: Penguin. p. 153.

- ↑ Gould, S.J. (1990), p.154}}

- ↑ Gould, Stephen Jay, & Eldredge, Niles (1977). "Punctuated equilibria: the tempo and mode of evolution reconsidered." Paleobiology 3 (2): 115-151. (p.145)

- ↑ Gould, S.J., & Eldredge, N. (1977) p.146

- ↑ Gould, S.J. (1995). "Stephen Jay Gould: "The Pattern of Life's History"". In Brockman, J.. The Third Culture. New York: Simon and Shuster. p. 60. ISBN 0-684-80359-3.

- ↑ Gould, Stephen Jay (2002). The Structure of Evolutionary Theory. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-674-00613-5. In his account of one ad hominem absurdity, Gould states on p.984 "I swear that I do not exaggerate" regarding the accusations of a Marxist plot.

See also

|

|

Further reading

- Dialectical Materialism, Alexander Spirkin

- Alexander Spirkin. Fundamentals of Philosophy. Translated from the Russian by Sergei Syrovatkin. Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1990.

- Spirkin's textbook offers a systematic exposition of the foundations of dialectical and historical materialism. The book was awarded a prize at a competition of textbooks for students of higher educational establishments.

- Ludwig Feuerbach and the End of Classical German Philosophy, Friedrich Engels

- Anti-Dühring, Friedrich Engels

- Dialectics of Nature, Friedrich Engels

- Materialism and Empirio-Criticism, V.I. Lenin

- On the Question of Dialectics, V.I. Lenin

- Dialectical and Historical Materialism, Joseph Stalin

- On Contradiction, Mao Zedong

- On the Materialist Dialectic, Louis Althusser

- Dialectical Materialism, V.G. Afanasyev

- Teodor Oizerman The main Trends in Philosophy. A Theoretical Analysis of the History of Philosophy. Translated by H. Campbell Creighton, M.A. (Oxon). Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1988. ISBN 5-01-000506-9

- The author traces the struggle between materialism and idealism on the basis of the dialectical-materialist conception of the history of philosophy. The book was awarded the Plekhanov prize under the decision of the USSR Academy of Sciences (1979).

- Materialism And Historical Materialism, Anton Pannekoek

- Reason in Revolt, Marxist Philosophy and Modern Science, Ted Grant and Alan Woods

- History and Class Consciousness, Georg Lukács

- Ioan, Petru "Logic and Dialectics" A.I. Cuza University Press, Iaşi 1998.

- "Dialectical Materialism", Theory and History, Ludwig von Mises

- The Origins of Dialectical Materialism, Z.A. Jordan

- Dialectics For Kids

- Dialectical Materialism: Its Laws, Categories, and Practice, Ira Gollobin, Petras Press, NY, 1986.

- Dialectics for the New Century, ed. Bertell Ollman and Tony Smith, Palgrave Macmillan, England, 2008.

- Rosa Lichtenstein's criticism of dialectical materialism,

External links

- @nti-dialectics – website presenting contemporary criticism of dialectical materialism

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||